Send Us Back Our Son

By Kinya Kaunjuga

“I think they are asking for my return,” I told my wife, Josephine as we sat down to eat dinner.

It had been a usual day at the hospital but the stares and flurry of activity my colleagues would engage in every time I walked by seemed exaggerated.

In fact, as I picked up a patient file from the nursing station, I was surprised to find the receptionist huddled in conversation with the nurses. Being the oldest employee at the hospital, the entire village knew she never left her desk which was in perfect view of the tv where her eyes remained glued even as she stamped patients’ cards and belted out their names.

As I reached for the file, their voices reduced to hushed tones. My suspicion that they were keeping something from me was confirmed when I walked outside during one of my breaks. Unaware of my presence, our pot-bellied hospital superintendent was staring at a fly on the wall as if wishing he could get that close to the ceiling fan to cool off in the midday heat.

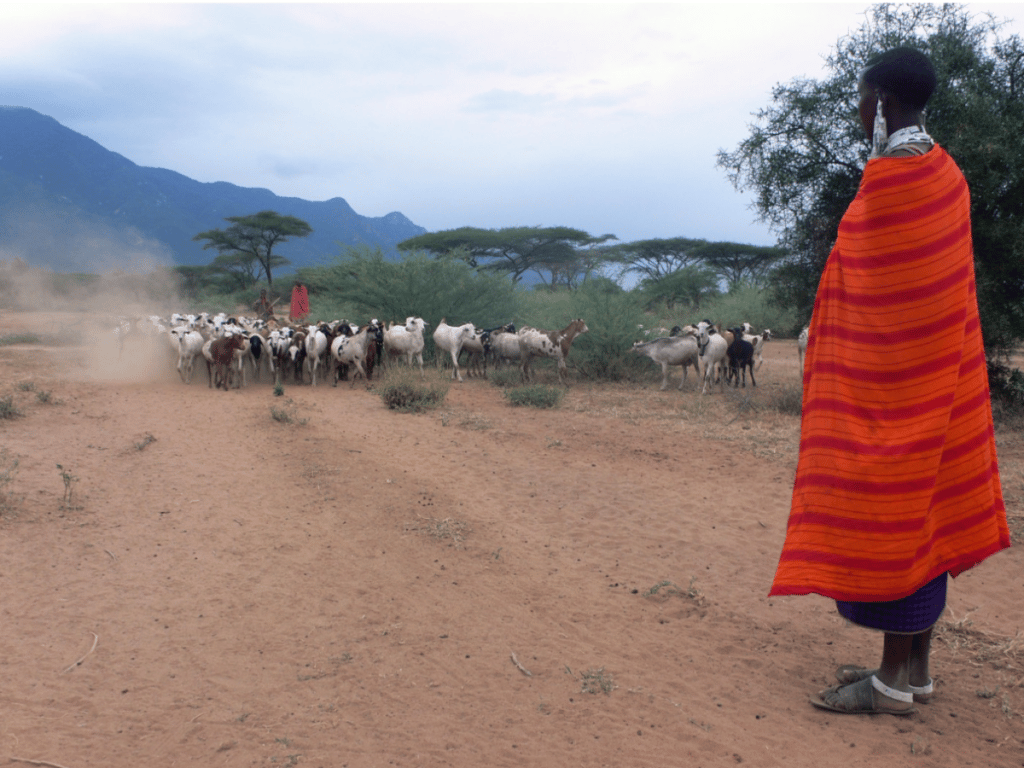

Since arriving in Narok county, he had taken a fancy to the local goat meat. No one blamed him, the goat meat here was renowned country-wide. Its naturally tender pink hue and irresistible salty flavor was caused by the thorny acacia bushes and alkaline water the goats fed on. The Maasai did not eat meat daily. They drank milk and cow blood, which sustained them during the long distances they walked their livestock in search of pasture.

I cleared my throat loudly and in an attempt at a cursory glance towards the noise, the superintendent swiveled and faced me. Over the past few years, his neck had gradually disappeared, seeming to leave his head planted immediately atop his stout body. His crestfallen expression at finding me there was quickly disguised with the jolly smile he always wore.

Yet looking closely it was unaccompanied by the hope-filled childlike twinkle in his eye that patients and staff had grown fond of. My instinct told me that the odd behavior I had witnessed all day was connected to whatever was weighing on his mind. As a medic in this cultural region, I had learnt to look at my patient’s eyes as I examined them. In spite of their brave smiles or positive greeting, a patient’s eyes could not hide how bad they were feeling. Our eyes are a window to our souls.

“If they want you to go back, you must. They gave you their blessing and sacrificed one of their morans to leave the village and go study. They need you now. I will prepare the children and items for the journey,” said Josephine.

That is how I came to Naikarra Medical Centre.

My colleagues had seen the moran clad in beads and our distinctive tribal red cloth draped over his shoulder obscuring a sheathed knife. By the time he was leaving the superintendent’s office, word had spread fast throughout the hospital.

Besides being covered entirely in caked dust that indicated he had walked during sunny and rainy days, his upright, tensed and focused physical stature sent fear down anyone’s spine that would try to stand in his way. Managing such energy and emotion under strain is taught to Maasai boys from as early as 8 years old when the rite of passage from childhood to moran takes place. They must be tough enough to protect their cattle, women, children and the elderly from rustlers, wild animals and tribal warfare.

Your commitment is making this happen!

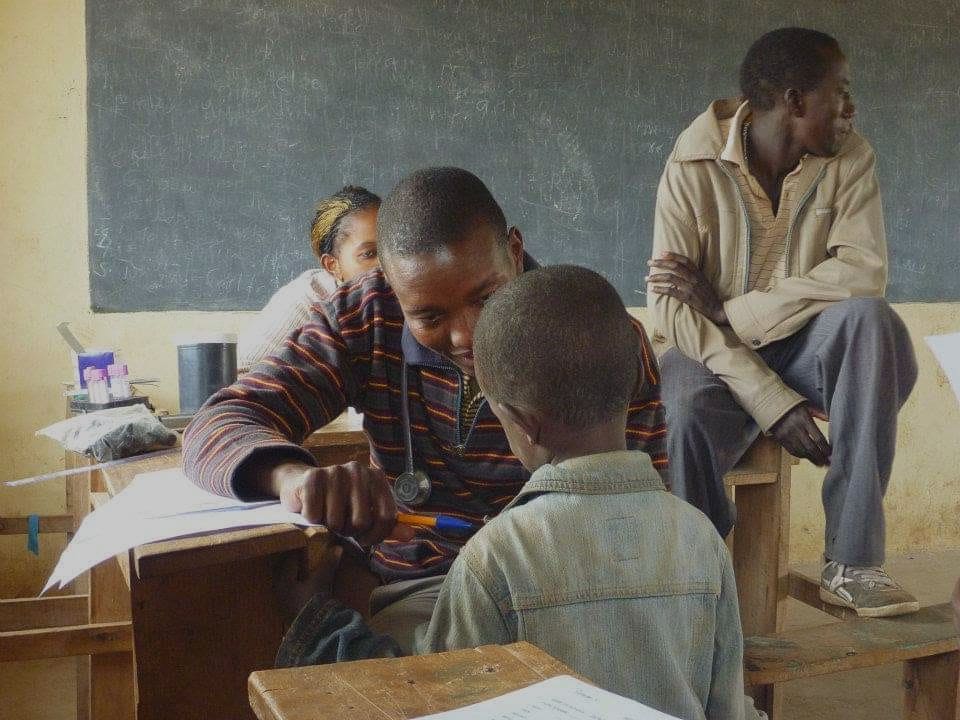

With your help BandaGo is now used in 71 clinics which have treated 410,860 patients in 3 countries.

Through BandaGo – our Health Management Information System, technology is actively helping medical clinics continue to provide good healthcare for those living in slums, informal settlements and remote villages like Naikarra. Thank you for being part of this journey with us, we couldn’t do it without you!

Kinya Kaunjuga

Kinya brings passion, an infectious laugh and 15 years of experience in the corporate and non-profit world to Banda Health. A Texas A&M alumni with a degree in Journalism and Economics, she says, "I love doing things that matter!"