Surviving the tides to treat on the ocean

By Kinya Kaunjuga

Legend has it that there was a lucrative and inimitable trade route from the Eastern Mediterranean to the African East coast. It was called the Indian Ocean trade. Sailors and merchants in dhows and proas would barter their wares for spices and exotic flora and fauna from the islands that dotted the world’s body of eastern waters even before reaching the mainland shores.

The trading resulted in a language called Swahili which is a mixture of Bantu and Arabic and is still used as the official national language of Kenya today.

As ocean trading stopped and boundaries crept in with colonization, the islands became obscure and forlorn. After all, their cowrie shells could not be compared to silver coins engraved with a crown, cytokinins hadn’t been discovered in coconut juice yet, and their untamed white sandy beaches didn’t stand a chance against the rich red soils found in central Kenya, which could grow “cash crops” for export.

Alas, and just like that, the islands were engulfed by a wave with a label that read, “poor and undeveloped.”

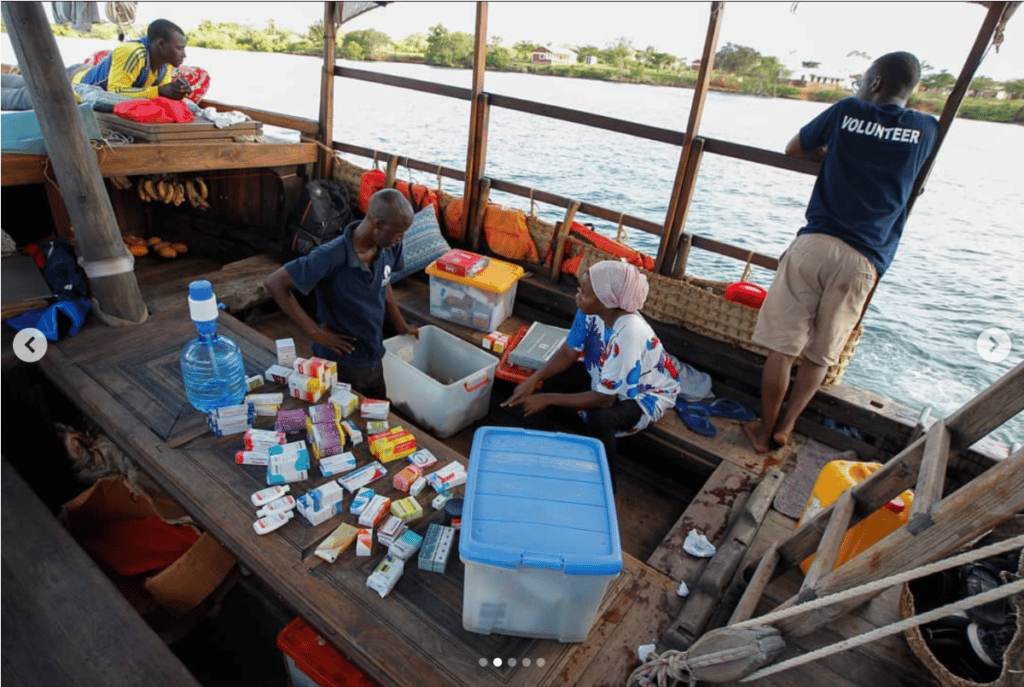

Despite not being a native to the coast, Jackson Mugambi, a clinical officer who has worked with SAFARI Doctors for the last two years, can now easily identify the perfect vessel to use at sea. This is a crucial part of his work in ensuring they reach the communities who live on the remotest islands.

On each trip, he must take into account how far he will need to carry medical equipment, medical drugs and his team. He has learned that on long trips deep into the ocean, selecting boats without engines is best. Engines rattle everything and have hard landings on choppy waters.

“Due to the heat combined with the sea, the waves have become taller and felt stronger than in the past decade.” Mugambi explains. He describes how wind blown sails on an old weathered dhow are perfect for their floating medical clinics. “A dhow is wide, slow moving and can even carry patients gently while they receive treatment.”

Of course the dhow is not as fast as a boat with an engine. But for centuries the Swahili coastal communities have used its indigenous Arab design to sail on the Indian Ocean just like when it was used for long-distance trading across two continents. And now the SAFARI Doctors are using it to treat those very communities.

Grab our next newsletter for the next chapter in this story on the SAFARI Doctors: “The wave that almost sunk us.”

We briefly leave the SAFARI Doctors surviving the tides on their boat clinic to mention some very exciting news!

Medical clinics using BandaGo have now treated half a million patients!

Let's go further.

Our technology is supporting medical clinics to provide good healthcare to people living on distant islands that dot the sea, in villages surrounded by wildlife, and in slums that no faint heart dares to visit.

And this far it’s made a difference in 500,000 patients’ lives from 3 countries in over 70 clinics because of your support!

Let’s go even further and with your help, reach our goal of treating 1 million patients in 150 clinics by the end of 2023!

Thank you for doing this with us. We simply couldn’t do it without each of you.

Did you know

The English words gumbo, goober, banana, yam, zombie, gorilla, canary, oasis and bark were borrowed from various African languages.

The Swahili Coast, an 1,800-mile stretch of Kenyan and Tanzanian coastline, has been the site of cultural and commercial exchanges between East Africa and the outside world – particularly the Middle East, Asia, and Europe – since at least the 2nd century A.D.

You can speak Swahili instantly! Jambo (Hello), Hakuna Matata (No problem or no ‘worries’) and Asante (Thank you).

$5000 helps us improve BandaGo and get it into another clinic

Kinya Kaunjuga

Kinya brings passion, an infectious laugh and 15 years of experience in the corporate and non-profit world to Banda Health. A Texas A&M alumni with a degree in Journalism and Economics, she says, "I love doing things that matter!"